How resources were held and managed in Māori society

Ko te āhua o te pupuritanga me te whakahaeretanga o ngā rawa i te ao Māori

Like tāne rangatira, wāhine rangatira played central roles in ensuring their communities had access to adequate resources, thereby building the economy, and ensuring prosperity and wellbeing for their people. Witnesses said that wāhine exercised significant influence on the collective management of resources, and played key roles in trading with other hapū and iwi – and, with the advent of colonisation, with Europeans.

Witnesses also emphasised the importance of tapu and noa in the effective management of resources – such as the collection of kaimoana, or in mara kai (for example, see Kayreen Tapuke, doc A94, pp 3-4).(external link) Marriages were another way that Māori communities secured resources, read more here.

From left: Alana Thomas, Wikitoria Makiha, Rukuwai Allen, and Aroha Herewini outside Terenga Parāoa Marae, July 2021

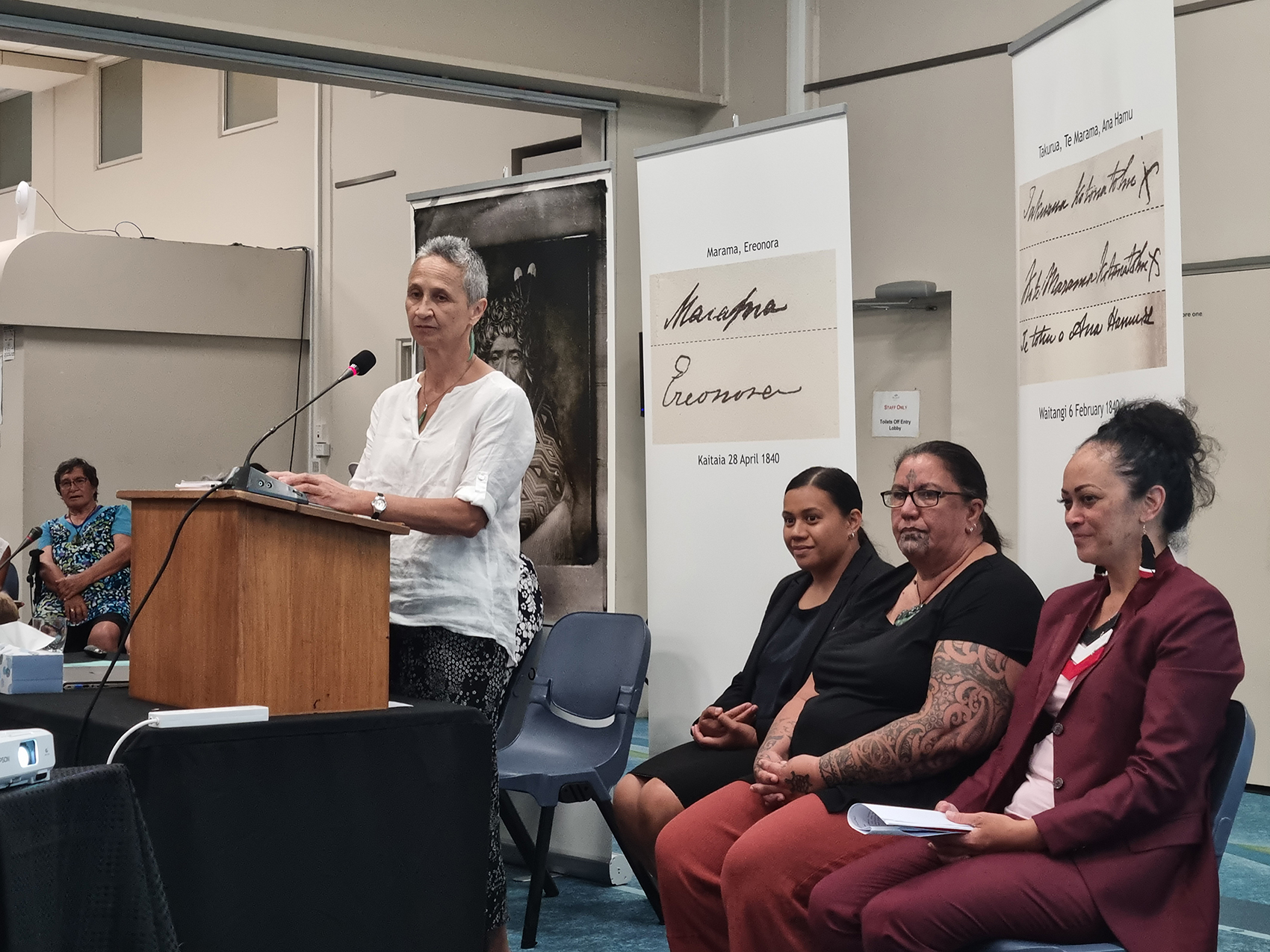

Key witnesses who gave evidence

Professor Angela Wanhalla (doc A82)(external link) has carried out archival research into writings from Māori women between the 1840s and 1870s. These writings show that, in pre-colonial Māori society, Māori women were key participants in political, cultural, social, and economic life, and made important decisions in relation to land. Professor Wanhalla detailed the crucial economic role wāhine Māori played from the 1790s until the 1830s, particularly in the significant South Island shore whaling industry in the 1830s. She explained how Māori communities promoted marriage alliances between newcomers and high-status wāhine in order to manage and derive benefits from the changing economic and social circumstances. Professor Wanhalla also emphasised the economic importance of women’s horticultural and food production knowledge, as well as their labour and cultural expertise in ensuring the survival and wellbeing of their whānau and communities – including the new shore whaling communities.

Professor Angela Wanhalla giving evidence virtually, pictured with Judge Sarah Reeves, September 2022

Michelle Marino (doc A111)(external link) explained how she understood her tīpuna to have managed food resources, particularly through mahinga kai, before colonisation. Ms Marino said she learned mahinga kai and fishing practices from her grandparents, who had in turn learned them from their grandparents.

Michelle Marino giving evidence at Waiwhetū Marae, Lower Hutt, August 2022

Whakataukī

- There are many whakataukī, or proverbs, used for food providers in pre-1840 Māori society. These whakataukī reflect strong leadership qualities, and are an expression of mana wahine. There are whakataukī for life bearers, as their tamariki and mokopuna are key to our future. Nga Wāhine are the house of humanity in the whanau, hapū and iwi worldview. They are respected for creating life. Some other whakataukī are as follows:

- Ko mahi Ko ora (work brings prosperity);

- Moea he tangata ringa raupa (marry a man with calloused hands);

- Nau te rourou, Naku te rourou, Ka ora ai te iwi (with your food basket and my food basket, the guests will have enough);

- Te wahine I te ringaringa me te waewae kakama, moea te wāhine whakangutungutu whakarerea atu (the women with active hands and feet, marry her, but the woman with overactive mouth, leave well alone);

- He aha te mea nui o te ao! He tangata, he tangata, he tangata (what is the most important thing in the word? It is people, it is people, it is people);

- Papatuanuku te matua o tangata (Mother Earth is humanity’s parent);

- He puta taua ki te tane, he whanau tamariki ki te wahine (as warfare is to men, childbearing is to women);

- He wahine, he whenua, ngaro ai te whenua (men die because of land and women); and

- Ko te mana o ia tangata, he tapu (the mana of each person is tapu). (Michelle Marino, doc A111, pp 3-4)(external link)

What witnesses said

- “In contrast to what we see today, women were traditionally not economically marginalised … I have heard some of our older generation [of Ngai Tamahaua] describe what life was like when they lived collectively on our marae at Ōpape … the community offered safety and benefit for all, especially women and children.” (Tracy Hillier, doc A92, pp 16-17)(external link)

- “Tikanga, cultural practice, was the foundation of social order, the expression of the values that ensured strong and resilient communities. Among these is koha, which is categorised as reciprocity or gift-exchange, the cornerstone of the political economy. [Janet] Davidson states that ‘… gift exchanges also served other social purposes, and a distinction has been drawn between economic and ceremonial gift exchange, according to whether the main motive for the transaction was the acquisition of goods or some wider social purpose.’” (Dr Ella Henry, doc A63, p 9)(external link)

- “Māori women occupy an extremely important role in the cosmological paradigms for, ‘[t]hey not only controlled the power, they also had the control of resources.’” (Dr Ella Henry, doc A63, p 7)(external link)

- “We had our own government, our own laws, our own language; we were communicating and trading with other iwi and with people across the Pacific. All along the way, our wahine were at the forefront of this, side by side with tane and often taking the lead. … Our rangatira wahine were in charge of trade and were at the forefront of lifting up and maintaining the mana of Ngapuhi hapū by forming alliances and supporting the thriving economy and wealth of our people. These wāhine traded resources but also korero too, and thus wahine facilitated the flow of information and ideas into Ngapuhi.” (Titewhai Harawira, doc A68, pp 5-6)(external link)

- “Hinewhare [the youngest daughter of Hongi Hika] settled in Te Rawhiti, where she traded water at Kariparipa with many sailing vessels, maintaining her mana whenua to that area. She was gifted in horticulture and created many opportunities for her hapū. She produced mara kai / cultivated food in areas that appeared to be sheer rock faces. She also grew a certain type of harakeke on these faces, binding this into rope. This was used to hang native gourds which were used as the containers for the water she sold. Furthermore, in inland areas such as Kāingahoa, Te Kokinga, and Wharau, Hinewhare grew extensive mara kai gardens which included taro, kūmara and rīwai, and which provided a source of wealth for the hapū. Ngare Raumati therefore had many successful trading ventures. This success, and the wellbeing of the hapū, was largely due to the knowledge, leadership and efforts of the wāhine, such as Hinewhare.” (Louisa Collier, doc A26(b), p 10)(external link)

- “Agriculture provided the means of growth and sustainability for the tribe. Wahine were often allocated roles to perform, manual duties required to ensure the variety of vegetation planted comes to full harvest and [were] tasked with the procedures needed to process and preserve produce throughout the seasons.” (Patricia Henare, doc A104, p 4)(external link)

- “Access to tribal resources and management of resources was commonplace for wāhine in our society to ensure the continued growth and wellbeing of our people. Ritihia [a Ngāruahinerangi tupuna, born in 1882] played an active role within a network of kuia who monitored and oversaw the wellbeing of whanau and iwi which often extended beyond our tribal boundaries. This included management and allocation of resources and support to whānau experiencing hardship.” (Ripeka Hudson, doc A128, p 15)(external link)

- “Mana wāhine held the knowledge. They understood the land and the resources and where to find things because those resources were theirs which they lovingly shared with the hapū. They were kaitiaki for the whānau, whenua, and hapū, ensuring future resources.” (Esme Sherwin, doc A110, p 7)(external link)

- “Between the 1790s and the 1830s, Māori welcomed traders and whalers into their communities and into their families. Māori communities managed and governed these newcomers through marriage alliances with women of status and mana. Marriage operated to fold new members into relational networks, and such relationships cemented the rights of whalers to establish stations on land, guaranteeing their protection. These rights were based on the authority and mana of Māori women, not that of Pākehā men. Women of rank married captains and station managers, other women worked as crew, station employees, and producers of key trade goods, while women’s horticultural knowledge was essential to survival. In these new communities, women developed and managed gardens, cultivated potatoes, wove baskets, gathered fish, managed marine resources, including fishing grounds, and scraped flax thereby sustaining their whānau and communities.” (Professor Angela Wanhalla, doc A82, p 6)(external link)

- “Shore whaling was an economically significant industry in 1830s Aotearoa, reflected in the numbers of whales successfully hunted and commodities exchanged. Māori communities derived wealth from their engagement with shore whaling. Women’s labour and cultural expertise helped to generate wealth for their communities through key trade items: potatoes and flax. They brought their expertise and skills in horticultural knowledge and the manufacture of valued items of exchange, especially whāriki, which were traded with whalers and visiting ships. The participation of Māori women in shore whaling during the 1830s demonstrates political leadership and diplomacy through their marriage alliances, their maritime and horticultural skills served the industry, and they were bearers of cultural knowledge, engaging in vital economic activities that enhanced collective wealth. Māori women’s engagement in the industry was made possible by a system of gender relations that asserted and supported women’s political and economic leadership.” (Professor Angela Wanhalla, doc A82, p 7)(external link)

- “[T]he knowledge, skills and experiences of these fishing practices prior to 1840 were passed down to my generation … These practices were passed down to both genders indiscriminately. There were no specified gender roles when it came to mahinga kai.” (Michelle Marino, doc A111, pp 4-5)(external link)