Gender and sexuality

Few witnesses explored the subject of gender and sexuality before colonisation. In part, this is likely due to what those witnesses who did speak on this topic noted: that colonisers sought to erase gender diversity and what they viewed as ‘deviant’ sexuality both in practice and from the historical record. Nevertheless, witnesses emphasised that gender and varied sexual expression existed in pre-colonial Māori society, pointing to surviving evidence of this in written texts (both by Māori and Pākehā), waiata, and carvings.

Key witnesses who gave evidence

Professor Leonie Pihama (docs A19 and A148) canvassed the ways colonisation has infringed upon sexual and gender diversity within te ao Māori. She argued that ‘[t]he colonisers redefining of what was deemed appropriate sexual behaviour and relationships is a part of the wider gender reorganisation that was integral to a colonising agenda to transform Māori society. It was also influenced by racial notions of sexuality where Indigenous expressions of diverse sexuality was consider uncivilised and savage’ (doc A19, p 34). Professor Pihama also discussed the historical and contemporary use of the term ‘takatāpui’ for Māori rainbow communities and individuals. She noted the historical story of Tūtanekai and his relationship with Tiki who is referred to as his takatāpui. Professor Pihama cited the work of Ngahuia Te Awekotuku MNZM who said:

For we do have one word, takatāpui. And ironically, this word is associated with one of the most romantic, glamourized [sic], man / woman love stories of the Māori world, the legend of Hinemoa and Tūtanekai. Tūtanekai, with his flute and his favourite intimate friend, his hoa takatāpui, Tiki, and Hinemoa, the determined, valorous, superbly athletic woman – my ancestress – who took the initiative herself, swam the midnight water of the lake to reach him, and interestingly, consciously and deliberately masqueraded as a man, as a warrior, to lure him to her arms. Isn’t that another, intriguing way which we, our community and tradition, have been denied? (Professor Leonie Pihama, doc A148, pp 5-6)

Professor Pihama submitted other relevant research to the Tribunal including:

- Honour Project Aotearoa report (document A148(a)); and(external link)

- Mana Wahine reader – article 29, ‘It’s About Whānau: Oppression Sexuality, and Mana by Kim McBree’ (document A148(c)).(external link)

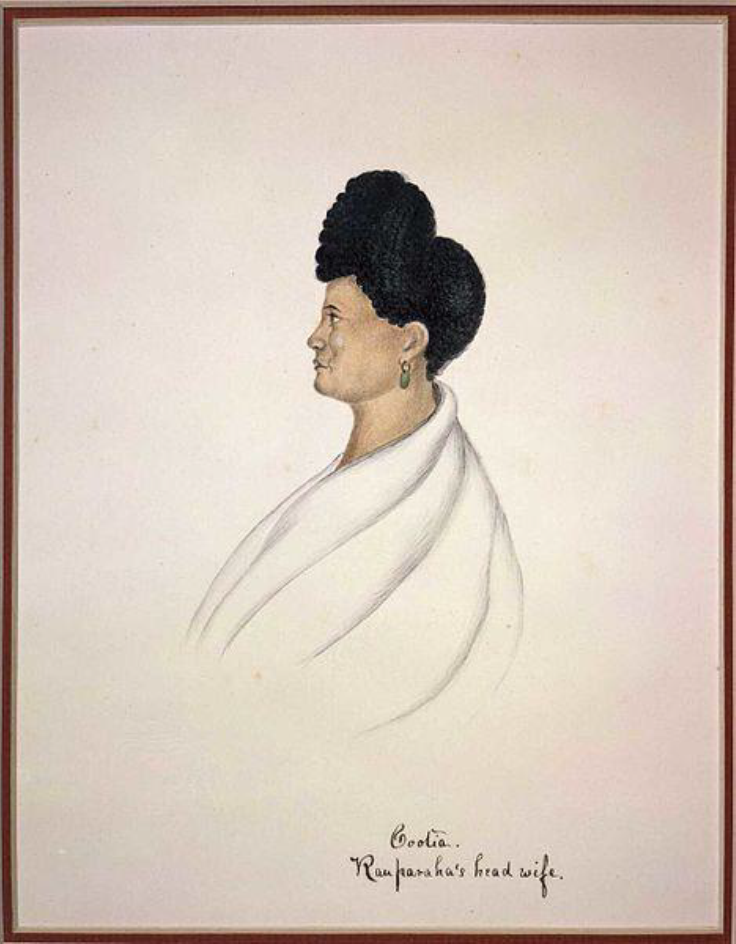

Professor Leonie Pihama giving evidence at Turner Centre, Kerikeri

Dr Byron Rangiwai (doc A146) gave evidence from the perspective of being both takatāpui and a member of Te Hāhi Mihinare. He drew from a wide range of writing from missionaries, ethnographers, and academics, to show examples of sexual and gender diversity within te ao Māori. He also detailed how the existence of this diversity, and its acceptance within te ao Māori, has been marginalised within the historical record. Dr Rangiwai said that ‘proof of non-heterosexual relationships in pre-colonial Māori society existed in carvings, many of which were destroyed by missionaries or taken away to museums in Europe … but one striking artefact which has survived is a mid to late 18th-century feather box or treasure box (papahou) held at the British Museum. This papahou is made up of sexual poses’ (pictured below).

What witnesses said

- “Evidence of bisexuality exists in a traditional waiata, published in an 1853 collection by George Grey, which mourns the loss of a young man. The text proclaims: ‘ko te tama i aitia, E tera wahine, e tera tangata.’ An English translation reads: ‘A youth who was sexual with that woman, with that man’. However, when the waiata was republished in 1928, the word aitia, which means to copulate, have sex, or make love was changed to awhitia, which means to embrace, hug, cuddle, or cherish.” (Byron Rangiwai, doc A146, p 5)(external link)

- “Joseph Banks, who accompanied Captain Cook, made some observations about Māori sexuality and gender diversity and made notes about a particular encounter with a person who appeared female but was biologically male … Missionaries, too, observed same-sex activities in Māori society.” (Byron Rangiwai, doc A146, p 6)(external link)

- “Regarding gender and sexual fluidity, there are stories of tohunga and renowned leaders who had same-sex relationships.” (Kayreen Tapuke, doc A94, p 10)(external link)

- “Genitalia were often depicted in ancestral carvings, as our tupuna reflected the rich reality of life, in an open and down-to-earth manner, in a way which celebrated the sexuality, reproductivity and divinity of both tāne and wāhine. The arrival of Victorian attitudes and judgments brought over from England led to the destruction of many of these carvings.” (Heeni Collins, doc A108, p 9)(external link)

- “Tera te ataahuatanga o te whakapapa Māori, kei roto i a tātou katoa tēnā magic. Kei roto tonu i ahau te ira wahine me te ira tane; kei te noho ēra mea e rua i te tangata kotahi. Ehara he mea ‘gender fluid’ tēnā; he mea tapu kē, tapu rawa; he hononga tēnā mai te tangata ki tōna whakapapa katoa me ngā wānanga, ngā kura kei roto. Ngā āhua katoa kei a ia.”

“What is so beautiful about Māori lineage that magic is within all of us. I have the female and male elements in me, those two elements can be in one person, it’s not about genderfluid. It’s about the tapu, the very sacredness, it’s a very connection of the people to all of their lineages and all of the houses of learning.” (Dayle Takitimu, doc A96, p 5(external link); Transcript 4.1.10, p 32) - “From an early age, children lived in close and intimate contact with adults. Their introduction to bodily functions and reproduction was part of their early education. Premarital sex was a norm, and young adults were allowed, even expected, to engage in sexual experimentation before settling down in a stable relationship.” (Ella Henry, doc A63, p 16)(external link)

- “We are certain that sex, and sexual relations, were considered to be extremely important in traditional Māori society … Māori sexuality, and its associated beliefs and practices, were fundamentally different from those of the 19th Century colonisers. It was not bound by the same social prohibitions, nor was it a means for men to control women’s lives, bodies and reproduction.” (Ella Henry, doc A63, pp 17-18)(external link)

- “I mua i te taenga mai o tauiwi ki Aotearoa ko te ai te ai. Ehara i te mea kino te ai. Kaare he kino mō te tāne i ai te tāne, kaare he kino mō te wahine ai wahine, kaare he kino mō te tama kia pērā ai ki te kohine i tukuna atu ki tetahi rangatira mo te ai.” (Hira Huata, doc A149, p 18)(external link)

"Before the arrival of Europeans to Aotearoa, sex was normal. It was not evil. It was common for men to have sex with men, or for women to have sex with each other, or for boys and girls to be given as sex toys for male and female chiefs." (Hira Huata, doc A149(a), p 11)(external link) - “There were Takataapui in the days of my kuia, I can remember meeting an old kuia who in her younger days built her own house. She lived with her whanau and they looked after each other. I will never forget the fact that it must’ve been so hard to do, and yet she did it. I am not sure about how Takataapui were treated in the days of my kuia. But I have read that they were usually accepted as part of the whanau, and therefore the hapu. I know that today takataapui whanau members are accepted as part of the whanau and people are more educated about diversity than they have ever been.” (Mereti Taipana, doc A130, p 8)(external link)

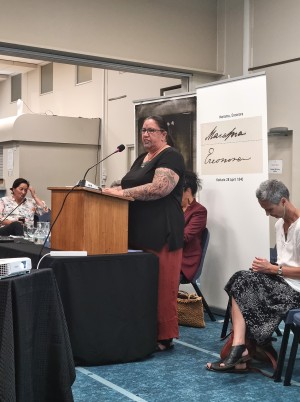

Dr Byron Rangiwai presenting evidence virtually, pictured with Judge Sarah Reeves