Expressions of mana wāhine in traditional Māori society

Ko ngā tauira e kitea ana mō te mana wahine ki te hapori Māori o mua?

Women exercised power, authority, and influence across various aspects of physical and spiritual life in traditional Māori society – indicated in the many examples given by witnesses in the tūāpapa hearings. Witnesses spoke about wāhine expressing mana in their roles as rangatira in whānau, hapū and iwi; through extraordinary deeds, and ordinary ones; through the array of mātauranga they possessed and passed on to the next generations; through maintaining and shaping whakapapa; through being kaitiaki of whenua; through their unions with tāne and with the spiritual world; and through birthing and raising the next generations.

Witnesses also said:

- wāhine played these roles based on their mana, not their gender.

- the possession of moko kauae by mana wāhine rangatira was a strong, visible example of their mana in traditional Māori society and today.

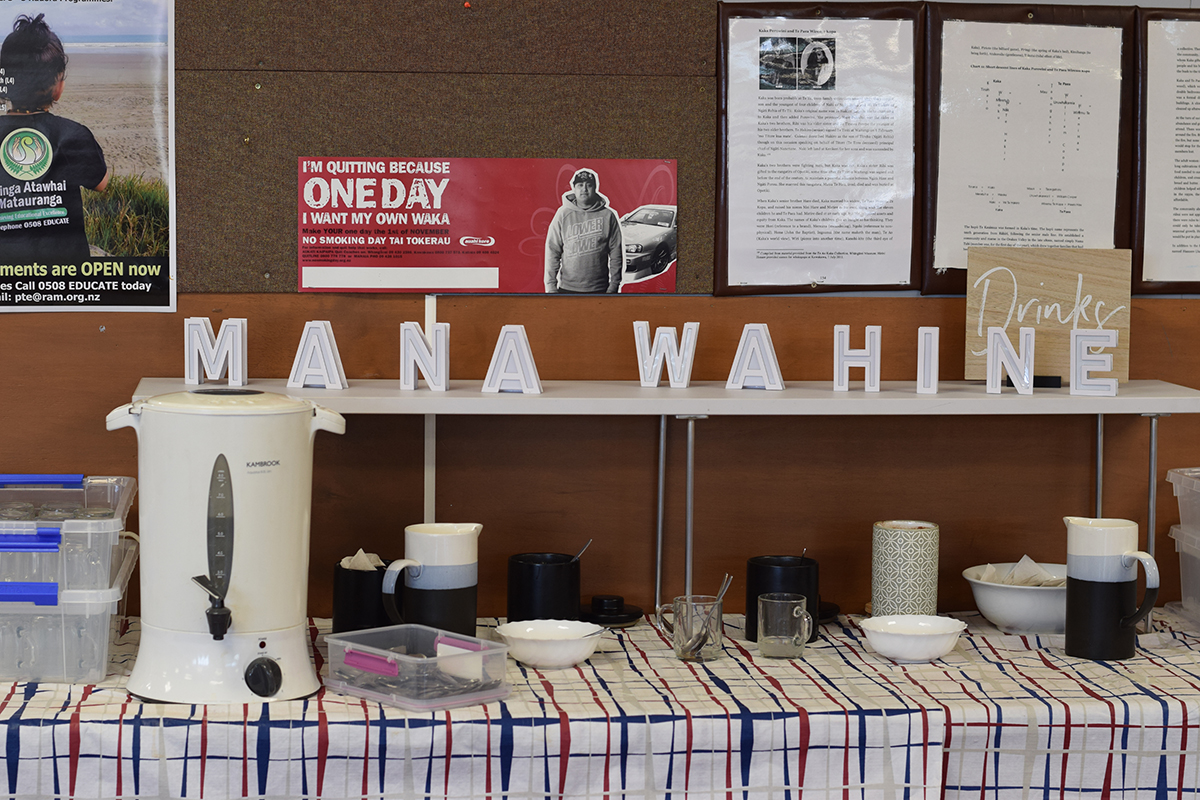

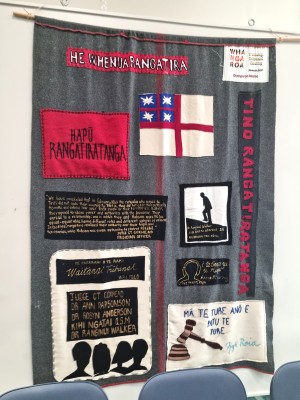

Blanket made by witnesses who appeared at hearing one, Turner Centre, Kerikeri, February 2021

Key witnesses who gave evidence

Te Kahautu Maxwell (doc A46) emphasised how the mana of wāhine is central in all his whakapapa lines – in Ngāi Tai, Tūhoe, Ngāti Awa, Ngāti Porou, and Ngāti Maniapoto.

Te Kahautu Maxwell giving evidence at Tūrangawaewae Marae, Ngāruawāhia

Dr Ani Mikaere (doc A17) told the Tribunal that the presence of themes of conception, gestation, and birth are common in the multitude of iwi accounts of creation, convey the significance of women for her tūpuna. She cited examples of these themes in the stories of Hineteiwaiwa, and her tipuna Waitohi, who exercised political authority in advising her brother Te Rauparaha.

Dr Ani Mikaere giving evidence at Turner Centre, Kerikeri

Hinemoa Ranginui-Mansell (doc A129) gave evidence about expressions of mana wāhine within Whanganui / Haunui-a-Pāpārangi whakapapa, including the several hapū, whare tūpuna, and kaitaki named after women, and the many waiata, kōrero tawhito, pūrākau, whakataukī and whare whakairo that reference wāhine. She explained that wāhine played a prominent role in political leadership in Whanganui society before colonisation, including being active in military campaigns and in peacemaking.

Tina Ngata (doc A88) presented evidence about the significance of wāhine within Ngāti Porou whakapapa, particularly Matakaoa. Ms Ngata said that while early ethnographers perceived traditional Māori society as patriarchal – informed by their own Eurocentric perspectives – even they observed the prevalence of female leadership in Tairāwhiti. Ms Ngata also described the landscape across Ngāti Porou as a testament to the significant role of wāhine, and noted the many hapū and whare named after wāhine throughout Tairāwhiti.

Tina Ngata giving evidence at Te Mānuka Tūtahi Marae, Whakatāne, pictured with Mereana Pitman (left)

Ripeka Hudson (doc A128) gave evidence about a number of significant women in the traditional narratives and whakapapa of her hapū, Ngāruahinerangi. They included Rongorongo, daughter of renowned Rangiātea tohunga Toto; and Ruaputahanga, who lived in the late sixteenth century and was instrumental in uniting the lineages of Aotea and Tainui.

Ripeka Hudson giving evidence at Waiwhetū Marae, Lower Hutt

Tiaho Mary Pillot (doc A91) presented evidence about significant women in Ngāti Hotu, based on stories told by her grandmother, Tiahuia Ruby Te Ahuru (1895-1971). They included Hinekapa, Hinemihi (born circa 1650), Rangikowaea Te Wharerangi (circa 1798 – 1886), and Te Maari II (1817-1829). Merle Maata Ormsby and Daniel Whetu Ormsby also gave evidence about the same tipuna.

Dennis Ngawhare (doc A117) described the centrality of wāhine to the whakapapa of Taranaki. He detailed the kōrero ‘Te Ara Tamawahine’, which refers to matrilineal whakapapa descent lines, and the lives of several significant Taranaki wāhine tīpuna – Rauhoto Tapairu, the tohunga Rahiri-mihia, the kuia Ueroa, and the leader Raumahora.

Dennis Ngawhare Pounamu giving evidence at Waiwhetū Marae, Lower Hutt

Hana Maxwell (doc A69) gave evidence about various female Ngātihau rangatira whose mana was acknowledged by various landmarks around the Ngātihau rohe, such as the waterfall on Pukepoto (Te Rere a Matamoe) that commemorates the birth of Matamoe. She also referred to several wāhine who advocated for various landblocks – including Hirana Paraha, who lived at Huiarau, the pā site on Ruapekapeka, and spoke for the Huiarau block in land court proceedings.

Hana Maxwell giving evidence at Terenga Parāoa Marae, Whangārei

What witnesses said

- “Apirana Mahuika opens his thesis on the female leaders of Ngati Porou by asking the question why so many hapū and so many marae and whare tipuna are named after women. The answer lay in their whakapapa which followed the principle of primogeniture, however, unlike the reports of other iwi in which the male line is followed – in Ngati Porou the female primogeniture line is also followed.” (Donna Awatere-Huata, doc A20, p 9)(external link)

- “There are tribal herstories of women who are remembered for their mana and deeds to their iwi and humankind. Women such as Waimirirangi, Maieke, Reitu and Reipae from the North and Wairaka from the Eastern Bay and wider Mataatua wielded immense influence, power and control.” (Ripeka Evans, doc A21, p 12)(external link)

- “In fact if you look across Ngāti Porou you will see that across our entire landscape, our people identify themselves through their female ancestors, and it is our female ancestors who have carried the mana whenua of our iwi. This is reflected in the numerous hapu, landmarks, wharenui and wharekai named after tipuna wahine.” (Tina Ngata, doc A88, p 5)(external link)

- “Our Wāhine were expected to develop roles beyond being mothers. We were strategists, military leaders, mediators, gatherers and hunters, midwives, warriors, healers, composers, political, weavers, landowners, mediators, gardeners, and balanced all of this within their spiritual domains.” (Paula Ormsby, doc A55, p 18)(external link)

- “In raupatu times due to the loss of the men, and two epidemics, four wāhine were recorded as leaders of the defenders of the whenua. These wāhine were Matarena, Te Reita, Wikitoria and Tiria. These wāhine were defenders of their whānau and hapu and their whenua and [this] is a reflection of the roles that wāhine held in precolonial times.” (Tracy Hillier, doc A92, p 18)(external link)

- “Women were politically active and played important roles in Māori political life, but cultural assumptions about politics as a male endeavour erased women from the archival record.” (Professor Angela Wanhalla, doc A82, p 2)(external link)

- “Māori women’s writing and testimonies from the post-1840 period often refer to their traditional roles as political and community leaders in earlier eras, and to female ancestors as exemplars. For these reasons, letters, petitions and testimonies created after 1840 are valuable measures for interpreting Māori women’s political and community leadership, their mana and authority, pre-1840.” (Professor Angela Wanhalla, doc A82, p 5)(external link)

- “Hundreds of petitions were sent to the government, many led by Māori women, over the nineteenth century. These also provide evidence of women’s political and community leadership. Women who possessed mana through illustrious whakapapa felt no qualms about speaking for their people: it was their responsibility to use this mana for the benefit of their people and often on a wider Māori stage and one way they did this was through collective petitions. The majority of these petitions emphasised that women had the ability to own land, direct its future, and to control it. Women were used to exerting authority in communities and over land.” (Professor Angela Wanhalla, doc A82, p 16)(external link)

- “Wāhine were crucial to the formation of the inter-hapu assemblies, known as Te Wakaminenga, that helped drive the unification of those who joined in declaring Māori tino rangatiratanga to the world.” (Titewhai Harawira, doc A68, p 5)(external link)

- “These tūpuna kuia of Taranaki demonstrate mana wahine in the traditional society of Te Ao Kohatu. Their examples show how important wahine were to maintaining and growing rangatiratanga over the whenua, of resources, of ceremony, of making war and for negotiating peace. They were exemplars of behaviour for their descendants.” (Dennis Ngawhare, doc A117, pp 3-4)(external link)

Mana was more important than gender

- “The status of rangatira was based upon merit not gender. The mana that it brought was not the authority to control, but the power and deep responsibility to protect.” (Titewhai Harawira, doc A68, p 3)(external link)

- “Leadership is not defined or circumscribed by gender in te ao Māori but can be inherited or achieved. There were female ariki, such as Ngāti Porou’s Hinematioro. Ngāti Porou scholar Api Mahuika says such women are assumed to be the exception to the rule of male leadership, but he argued that evidence from tribal whakapapa and traditions show this is not the case. He gives the example of hapū named for female ancestors: Ngāti Hinepare, for instance, derive their mana through tracing descent from this female ancestor and Ngāti Hinerupe are named for a woman who displayed personal qualities of leadership.” (Professor Angela Wanhalla, doc A82, p 4)(external link)

- “When studying whakapapa lines, without scrutiny, it is easy to get genders confused because the language is non-gendered and difficult to know whether the names are male or female, unlike western naming which operates along different lines. Western genealogical records invariably invisibilise and silence women (undertaken as a norm in Western history) and that practice of invisibilising through silencing has culminated in women’s exclusion from power. But roles were much more fluid and less gendered in Māori societies.” (Mere Skerrett, doc A137, pp 8-9)(external link)

- “A great deal has been written about Māori leadership, and much of that has implied a quite distinct gender qualification. That is, Māori leadership, in terms of day-to-day control and authority, has been defined as a primarily male domain. … However, if we look at other works we are offered alternative perspectives. For example, Mahuika has written about the Ngati Porou experience. He points out that early writers focused attention on primogeniture through male lines as a precursor for leadership, and presents the case of his own tribe, where leadership is both inherited through senior female lines, and leadership by women has been achieved.” (Dr Ella Henry, doc A63, p 28)(external link)

- “Unlike the colonised treatment of history where patriarchy has (and continues to have) paramountcy, in pre-colonial Taranaki Māori society gender was not a determinative feature of mana or status. Rather, the distinctive roles of tāne and wāhine each contributed to the wellbeing of their whānau, hapū and iwi. There is little evidence that mana was solely centred around a hierarchical concept of leadership, that is, via a single autocratic leader model. Mana was way more varied and complex that that and was also determined by what Taranaki Māori communities prioritised and valued.” (Aroaro Tamati, doc A131, p 2)(external link)

- “Women were accorded mana through their actions and behaviours in addition to their inherited mana, in much the same way as men were.” (Tina Ngata, doc A88, p 6)(external link)

Moko kauae: an expression of mana wāhine

Several witnesses shared that moko kauae were a visible manifestation of the mana and status held by wāhine in their whānau, hapū, and communities. For instance, some referred to Muriwai as having tāmoko which reflected her status as a rangatira. However, witnesses also said that knowledge and understanding of the practice of moko kauae diminished as a result of colonisation.

Key witnesses who gave evidence

Christine Harvey and Rangi Kipa (doc A147) are moko kauae practitioners who provided joint evidence about the origins and significance of moko kauae. They described moko – along with many other artistic practices and cultural forms in te ao Māori – as language systems expressing societal norms and values, as well as the interconnectedness of people to the environment and one another. Ms Harvey also described the pain and disconnection experienced by iwi, hapū, and whānau due to suppression of moko kauae practices.

Rangi Kipa giving evidence virtually, pictured with Judge Sarah Reeves

Christine Harvey being supported by waiata at Ngā Hau E Whā, Christchurch

What witnesses said

- “Nō te wahine te mana tō te Moko, nō Niwareka kē te taonga e mauria mai ki te Ao Turoa nei. Mai tōnā whakapapa kē tēnei taonga tuku iho … He nui ake ngā āhuatanga o te Mana Wahine heoi ko te kauae he tohu mutunga o te pai kia kite ai tātou katoa. Ehara noa mō te tokoiti hē tohu mana tō ia wāhine Māori. E tae wahine mai. He tohu kia tū wahine, me tiakina hoki kia ora kia haumaru nā te mea he whare tangata.” (Rangi Kipa and Christine Harvey, doc A147, p 4)(external link)

"Women exercise mana over moko because it was Niwareka who brought it here to the natural world. This ancestral treasure descends from her. ... There are many more aspects of Mana Wāhine but the most potent symbol is the chin moko which can be seen by everyone. It’s a powerful symbol for all Māori women not just a few. Come forth women. It urges women to stand and protect it so that it survives and is safe because they are the house of humanity." (Rangi Kipa and Christine Harvey, doc A147(b), pp 1-2)(external link) - “[Moko are] language systems that perpetuate and maintain our societal norms that convey and carry our collective (but not limited to) ethics, values, norms, morals and codes of conduct.” (Rangi Kipa and Christine Harvey, doc A147, p 7)(external link)

- “[Kauae] was only a small part of the diverse practises of body adornment and modification, it is well documented in early lithographs from Cook and other voyages that Wahine Maaori wore moko of all descriptions on all parts of their bodies.” (Rangi Kipa and Christine Harvey, doc A147, p 8)(external link)

- “The distinction of rank is usually recorded in the tāmoko, enabling the mana and status of the wearer to be reflected. These include warfare skills, ability to unite confederation of tribes, whakapapa, high birth and history.” (Raiha Ruwhiu, doc A93, pp 6-7)(external link)

- “There may be occasions when tāmoko may be changed. An example of this is during the exploits of war, where the ultimate insult is for the enemy to change the tāmoko … A replica pou in the Opotiki museum shows Muriwai had a full tāmoko, full facial, arms, buttocks, thighs, legs like that of a male, there was no differentiation, which confirms her role as a wahine whaikorero, wahine whai mana. What I have observed is that the last moko kauae in our whanau and the hapu of Ngai Tamahaua is my great grandmother Hariata Parekaramu’s generation. There are many nannies with moko kauae in the photos that adorn the walls in our ancestral house Muriwai, but I am not sure of what generation they belonged to. One can assume that our Ngai Tamahaua definitely had women that were deserving, skilled, in matauranga Māori. My mother believed that moko kauae were reserved for those with a kauae runga practice, so she didn’t see the relevance of moko kauae with the evolving culture, especially given that the English language had changed the thinking and psyche of individuals. I often wondered whether the church had impacted her comments, or that the Anglican and Catholic church were exerting their dominance through Christianity telling Māori that tāmoko originates from the underworld and backing it with scripture.” (Raiha Ruwhiu, doc A93, pp 12-13)(external link)

- “The consistent practice of applying tribal markings, moko kauae, on wāhine Māori had been absent from Taranaki hapū and iwi for over a century. The dearth of tā moko practice is directly attributed to colonial confiscations, behaviour and practices and the negative effects experienced by wahine Māori in Taranaki.” (Ngaropi Cameron, doc A113, p 11)(external link)

- “Either as an adolescent or a young woman Mihi Ki Turangi (b 1836) got her Moko Kauae. It is in the design of Maniapoto, she had her lips done and has a line above her top lip.” (Mereti Taipana, doc A130, p 4)(external link)