Wāhine in their whānau, hapū and communities: maintaining and protecting mana

Ko ngā wahine ki roto i ō rātou whānau, ō rātou hapū, ō rātou hapori anō hoki: e puritia ana, e tautiakihia ana te mana

Witnesses explained that it was whakapapa and mana, not gender, that shaped communities in traditional Māori society. As such, wāhine played key roles in upholding the mana of their whānau, hapū, and communities. Witnesses explained that tīpuna wāhine were often peacemakers in conflicts or active participants in military campaigns, in order to ensure the continuity of hapū.

Rōpū from the Mana Wāhine (Pihama and others) (Wai 2872) claim at Turner Centre, Kerikeri

What witnesses said

- “In our tātai hono are all the stories of [wāhine] ability and our position to make decisions of great importance to our hapū and our marae.” (Moe Milne, doc A62, p 10)(external link)

- “Hine-ā-Maru led her people to a place where they could thrive and grow – believing that each person had a role to play in the overall health and wellbeing of the hapū. It is now for us to carry that legacy forward; to pursue a means where our whānau and hapū are supported to prosper and do well so they can do the best job of raising our tamariki.” (Moe Milne, doc A62, p 28)(external link)

- “[Muriwai] held great responsibility for all the personnel within her confederation: for their health and well-being, psychological welfare and spiritual guidance. She was expected to be a strategist, involved in warfare as well as implementing conflict resolution.” (Raiha Ruwhiu, doc A93, p 4)(external link)

- “One way of looking at mana is leadership and decision-making for the hapu. You have to have whakapapa and ahi kaa to carry mana in the context of being able to make decisions for us here at home. Women have been central to this.” (Tracy Hillier, doc A92, p 16)(external link)

- “Wāhine Māori played a prominent role in traditional Whanganui society. Wāhine Māori were political leaders who exercised considerable power within their hapu and iwi – and were active in military and political campaigns and in the community. Women played roles both of instigators and peacemakers during tribal welfare and were able to turn situations from a sacred space back into an ordinary space.” (Hinemoa Ranginui-Mansell, doc A129, p 7)(external link)

- “Prior to 1840 and the first missionary's arrival to Aotearoa, wāhine held predominate roles within society. They were not thought of as less in comparison to their male counterparts … They held positions of power, and some were chiefs among their iwi.” (Merepeka Raukawa-Tait, doc A95, p 3)(external link)

- “Just like my kuia was, I was raised within my whānau, hapū and iwi to know that it was the wāhine’s job to ensure that everybody was in good health, and that everything was running smoothly. Our job was to ensure the maintenance and the protection of the mana of our community. It was to ensure that the people behaved accordingly. That was of the utmost importance.” (Paihere Clarke, doc A141, pp 5-6)(external link)

- “[Kuia] would gladly and graciously give themselves on behalf of the protection, safety and security of the whānau, pā, marae, papakāinga, whenua tuku iho, taonga and wahi tapu. This is all part of our role as mana wahine. The younger childbearing wahine would be protected further back in the social and physical infrastructure of the whānau and hapū, in order to continue the chiefly ariki rangatira bloodline.” (Aorangi Kawiti, doc A24(a), pp 9-10)(external link)

- “Historically we were rangatira in our own right. We were owners of vast tracts of land. We held equal status with men. We were healers, educators, midwives, decision makers in the affairs of the hapū and iwi, warriors, matakite, tohunga, kaitiaki of the sacred knowledge and much much more.” (Deirdre Nehua, doc A25, p 5)(external link)

- “Women had their own whakapapa so they could take from either male lines or female lines – the distaff line. In my experience with Maori, the male line did not automatically sit above the female line. You could take a female line if it were more important than the males. There are times in my own family, where my female line is far more important than my husband’s line. For example, when dealing with land blocks in Te Arawa, my family do not call on their Hokianga whakapapa, they call on their Te Arawa/Whakarewarewa whakakpapa. The line they will call on depends on the land they are standing on. There was no concept of inferiority of the women’s role, the only question is what is likely to result in the best position to help the hapu achieve its goals.” (Kaa Kereama, doc A14, pp 1-2)(external link)

Wāhine involvement in warfare

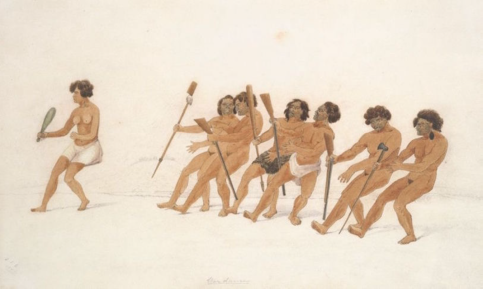

Witnesses said that war was not exclusively a male domain and wāhine took part in warfare to protect the mana of their communities. Witnesses told stories of wāhine who were involved in fighting, and also described wāhine as leaders in their communities during periods of war.

Haka party at Rotorua 1901, photographed by W.H.T. Partington, from Alexander Turnbull Library collection (pictured in document A67(e))

War dance, by Thomas John Grant (1851) (pictured in document A67(e))

What witnesses said

- “Wāhine Māori were political leaders who exercised considerable power within their hapu and iwi and were active in military and political campaigns and in the community.” (Hinemoa Ranginui-Mansell, doc A129, p 7)(external link)

- “In Waitohi’s time and iwi … it was common for wāhine to be political and military strategists. In fact, in Ngāti Toa Rangatira, wāhine were considered the best strategists. Women held big roles in terms of warfare, that strategist mātauranga was carried by them.” (Elaine Bevan, Heeni Wilson and Nganeko Wilson, doc A119, p 4)(external link)

- “The conventions related to peace making included the exchanging of weapons, known as tatau pounamu. This was known as the ‘male peace’, sometimes referred to as the rongo marae because it was concluded after discussion on the marae, of which [Ranginui] Walker states: ‘A male peace … could be abrogated by either party when it suited them. A more enduring peace was a woman’s peace, where women were exchanged with the victors.’ The latter was known as the rongo wahine, or woman’s peace.” (Dr Ella Henry, doc A63, p 26)(external link)

- “Women warriors were known as wahine toa, and the literature identifies varying levels of their involvement in warfare … In fact, the poi dance was not only a game to encourage dexterity and grace. It helped strengthen wrists for martial arts, particularly in the use of mau patu, the single-handed weapons.” (Dr Ella Henry, doc A63, p 27)(external link)

- “Women were part of traditional war parties, for example at Marae Totara. We have a haka that shows that women were a part of this war party.” (Tracy Hillier, doc A92, p 17)(external link)

- “Wāhine Māori were warriors that fought alongside the men. One example of a formidable wāhine was Hongi Hika’s wife, Turi Katuku. She was a warrior. She went into battle in wars where Hongi Hika fought. She was a fierce battlefield strategist. Her knowledge about the Europeans’ war tactics was deadly effective in battle. She also happened to be blind. It is said that Hongi Hika would return to her at night and weep to her about what he saw in battle.” (Violet Walker, doc A66, p 9)(external link)

- “There was an occasion when all the menfolk of our pā had gone off to fight in a battle. This left only women home in the kāinga. A group of male taua appeared at the pā, ready to destroy their kāinga. The women immediately took a stance of retaliation, and were successful in fighting and warding off that taua. Word got around the region that these women had successfully stood and fought for their kainga and their whānau – they were then given the accolade that they stood and fought: I tuu kā riri. The name Tūkāriri became their family name from then onwards.” (Patricia Tauroa, doc A60, p 22)(external link)

- “In pre-colonial times warriors were named after their mothers and grandmothers, taking on their mana and tapu. Male warriors named their weapons after their mothers and grandmothers. These examples indicate an acknowledgement and celebration of the mana of wahine as a primary source of identity (and also shield of protection).” (Dr Ngahuia Murphy, doc A67, p 4)(external link)

- “In Mataatua, the battle of Te Tapiri provides a historic example of the mana of wahine in traditional society. The Ngāi Tūhoe contingent was led by the kuia Maraea Tu te Maota. She conducted the war rites. She fought on the front line, pretending to catch bullets that flew past her. Not a shot was fired on the Tūhoe side before the arrival of this ‘prophetess’ on the battlefield. The Ngāti Manawa side was led by Hinekou. She conducted the karakia and rituals on the battlefield. Her visions directed the battle strategy. A huge portion of the fighting Ngāti Manawa force were wāhine. This example challenges dominant narratives that there were no female tohunga. Indeed there were and they held huge mana.” (Dr Ngahuia Murphy, doc A67, p 7)(external link)

- “Women played roles both of instigators and peacemakers during tribal welfare and were able to turn situations from a sacred space back into an ordinary space. Hinengakau married Tamahina of the neighbouring Ngāti Tūwharetoa in a peacemaking alliance.” (Hinemoa Ranginui-Mansell, doc A129, p 7)(external link)

- “About 1821, the musket-armed taua known as Te Amiowhenua travelled down the east coast to Te Whanganui-a-Tara. From Te Whanganui-a-Tara, the armed men moved up the west coast to Whanganui. A woman there called Kōrako (the mother of Hakaraia Kōrako of Ngā Poutama) lured the taua upriver to Mangatoa near Koriniti (Corinth, formerly named Ōtūkōpiri), where Whanganui fighters led by Te Anaua surrounded them. Te Anaua and his men prevailed, trapping the invaders in a narrow gorge and inflicting heavy losses.” (Hinemoa Ranginui-Mansell, doc A129, pp 7-8)(external link)

- “Ko ngā wāhine whai mana o roto ia Ngāti Pikiao, he wahine i whakaakonahia i roto i te Whare Tū-Taua e kīia ana ko Manini-aro. He wānanga teneki i whakatūria ai e Ngāti Tarāwhai mō Te Arawa katoa. Ko wētahi o wāna akongo ko Hineheru. Koia te tamāhine a Te Rangitakaroro – te mātāmua o ngā tamariki a Tarawhai. He wahine tū ki roto i ngā ope taua o Ngāti Tarawhai rāua ko Ngāti Rongomai, puta atu ki a Ngāti Pikiao hoki. Nā reira, koia tērā ka whai atu i ngā mea tāne o te iwi ki ngā pakanga. Koia anō hoki tētahi o te hunga whakahau me te whakapakari ake i ngā tāngata o te tū taua. E hia kē nei ngā pakanga i haere ngātahi atu ai a ia, nā, ka riro ano hoki ki a ia te hōnore o te pakanga i tōna patunga i ngā rangatira o te hoariri. Nā runga i tōna māia me tōna kaha, ka riro ki a ia te tūnga Rangataua.” (Timitepō Hohepa, doc A90, p 5)(external link)

"The most powerful women in Ngāti Pikiao were taught in the Ancient School of Martial Arts called Manini-raro, which was a school established by Ngāti Tarāwhai for all of Te Arawa. One of its students was Hineheru, daughter of Te Rangitakaroro who was the eldest child of Tarāwhai. Hineheru fought with the war parties of Ngāti Tarāwhai and Ngāti Rongomai, including Ngāti Pikiao. And so she went to battle alongside the men of the iwi. She was also a commander and trained the warriors. She fought at many battles and was honoured for killing enemy leaders. Because of her courage and strength, the position of Rangataua was bestowed upon her." (Timitepō Hohepa, doc A90(a), p 5)(external link)