Life in today's world

A Loss of Mana

The mana of the Te Roroa chiefs was related to their ability to control their main economic resource - the land - for the benefit of the tribe. By the 1920s, they had lost most of their land.

Map of the Waipoua settlement [GIF, 146 KB]

Some of the consequences were:

- the tribe's economic base was lost;

- access to traditional mahinga kai was lost;

- Te Roroa's ready access to their spiritual base in the Waipoua kauri forest was lost;

- the land was used in different ways, resulting in ecological damage; and

- wahi tapu became accessible to the general public, violating the sacred nature of these places.

Life in Waipoua

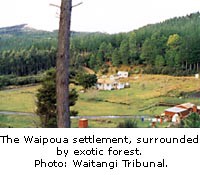

When the Te Roroa people sold their land, they expected in return to have roads and schools constructed, and to become less isolated from the rest of the country. Roads were built inland between Katui and Waimamaku, and to the Waipoua Forest head-quarters, but they bypassed the Waipoua settlement. The accompanying map (right) shows how isolated this settlement was.

The Waipoua settlement had no electricity, telephone, or postal services. The people travelled to the forest headquarters to collect their mail and use the telephone. Electricity was not supplied to the settlement on the grounds that it would create a fire hazard for the forest and would be a nuisance during logging operations. No water supply or sewer-age system was installed.

Te Roroa donated land to the Crown for a school in 1939. A school was eventually built, but it was closed down after a few years because the rolls were too low.

Regular medical and dental care for the Waipoua settlement ceased when the native school closed down in 1956. Thereafter, a doctor and nurse visited the settlement only about every six weeks.

Te Roroa's Attempts to Have their Grievances Heard

It was some years after the land sales, when the land was opened up by the Crown for sale to others for settlement, farming, and forestry, that Te Roroa realised that they had lost their land for good. Ever since then, they put their case to the Government, asking for the return of the land they intended to be kept out of the sales. Different governments made different responses:

- During the lifetime of those who sold the land, the Government did nothing.

- In 1908, the Stout-Ngata commission recommended turning some Te Roroa wahi tapu into reserves. But by then it was too late - most of the land had been sold into private hands.

- In 1939, the Government established the Acheson inquiry to look closely at the history of the land sales. The inquiry concluded: 'The circumstances of this case … cry aloud for redress. The two reserves (Manuwhetai and Whangaiariki) are theirs and should be returned to them, no matter what cost to the Crown this may involve.' But the Government did nothing.

- In 1986, Te Roroa first approached the Waitangi Tribunal to ask it to investigate the improper sale of the Maunganui block. By 1990, they had lodged a full statement of claim covering all their grievances.

Next: The Tribunal Findings

This page was last updated: