The significance of te whare tangata for the mana of wāhine

Ko te hirahiratanga o te whare tangata ki te mana o te wāhine?

Witnesses shared pūrākau, karakia, waiata, pepeha, haka, poems, and stories about tūpuna that showed the high status of te whare tangata in pre-colonial Māori life. Through te whare tangata (the womb, literally ‘the house of humanity’), wāhine upheld whakapapa; linking humanity to the atua and to the whenua. Many social practices reflected the significance of te whare tangata, such as māu rākau, marae protocols, tāne caring for menstruating wāhine, male midwifery, and tāne tucking ikura (menstrual blood) into their belts for courage in war. Witnesses also emphasised, however, that the mana of wāhine was defined by more than te whare tangata.

Key witnesses who gave evidence

Dr Ngahuia Murphy (doc A67)(external link) told the Tribunal about her pioneering research, some of which is published in He Awa Atua: Menstruation in the Pre-Colonial Māori World (2013).(external link) Dr Murphy told the Tribunal about the centrality of te whare tangata to Māori ways of being and to the mana of wāhine – both before colonisation and in the present day. Dr Murphy described various menstruation, puberty, pregnancy, and birth rituals, karakia, and ceremonies that reinforced the significance of te whare tangata for the mana of wāhine. These practices demonstrated her tūpuna’s belief that, through te whare tangata, wāhine bridged life and death, connected humanity to the atua and whenua, and acted as kaitiaki to whakapapa.

Dr Ngahuia Murphy (left) pictured with Annette Sykes, Camille Houia, Te Rangitunoa Black

Patricia Tauroa (doc A60)(external link) shared her view that possessing te whare tangata imposed certain responsibilities and expectations on wāhine Māori. For instance, she said that particular rōngoa and mātauranga would not be practised by a woman of childbearing age in order to protect te whare tangata. She also described how women past childbearing age are still responsible for upholding mātauranga relevant to te whare tangata to pass on to the next generation. Men bore responsibilities too, not only for creating new life but also for caring for the wellbeing of parents and children.

Patricia Tauroa giving evidence virtually, pictured with Judge Sarah Reeves

Jessica Williams (doc A61)(external link) described her journey of reclaiming knowledge about mau rākau. She described how many mau rākau moves are based around te whare tangata, aiming to protect it, to ensure the continuation of whakapapa and maintain connections with tūpuna, whānau, whenua, hapū and marae.

Jessica Williams giving evidence at Terenga Parāoa Marae, Whangārei, pictured with whānau

Hinewirangi Morgan (doc A40)(external link) expressed the power of te whare tangata through a poem entitled ‘Five Kuia / Grandmothers ago’.

Hinewīrangi Morgan (centre, wearing grey) pictured with whānau

Dr Ani Mikaere (doc A17)(external link) described how Te Rauparaha’s haka ‘Kīkiki Kākaka’ positions te whare tangata as ‘the transitional space between Te Ao Mārama and Te Pō’.

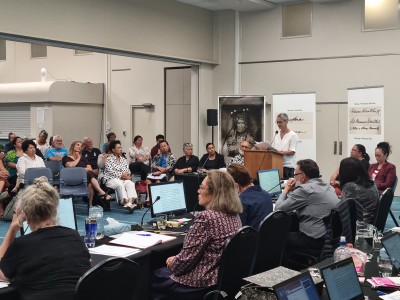

Dr Ani Mikaere addressing panel and audience at Turner Centre, Kerikeri

What witnesses said

- “He wahine, he whenua. Women are the human counterpart of Papatūānuku. We are the ūkaipō, providing, like the whenua, for all the needs of humanity born from our wombs. The whare tangata is the kaitiaki of the ira tangata, of humanity, counting and shaping the generations, born and nursed from her body.” (Dr Ngahuia Murphy, doc A67, pp 2-3)(external link)

- “The way that Māui met his death (from Hinenuitepō) confirms, in no uncertain terms, the unassailable power of the whare tangata. Māui’s chosen strategy to achieve immortality—attempting to reverse the birthing process—is also significant. It clearly establishes the birth canal as a two-way conduit between Te Pō and Te Ao Mārama. Our creation theories establish the centrality of women to whānau, hapū and iwi, positioning them as agents of transition: between the physical and the metaphysical, between the unconscious and the conscious, between tapu and noa states, between life and death.” (Dr Ani Mikaere, doc A17, p 4)(external link)

- “The story behind [the composition Kīkiki Kākaka] is well-known. While being pursued by a group from Waikato, Te Rauparaha asked for Te Heuheu’s assistance and was sent to Rotoaira with instructions to seek help from Wharerangi. Wharerangi hid Te Rauparaha in a kūmara pit and placed Te Rangikoaea over the mouth of the pit. When Te Rauparaha’s pursuers arrived at Rotoaira, Wharerangi told them that Te Rauparaha had been and gone. Doubting the truth of this statement, the group from Waikato searched the village, their tohunga reciting karakia as they went. It is generally understood that the power of the karakia was counteracted by Te Rangikoaea, her whare tangata preventing Te Rauparaha from being detected and thereby saving his life. The description of Te Rauparaha crouched inside the kūmara pit while Te Rangikoaea straddles the mouth of this small, enclosed space, conjures up a powerful image of the pit as an extension of the whare tangata. It is the ability of the whare tangata to remain intact in the face of potential intrusion by the karakia that determines Te Rauparaha’s chances of survival. From the words he used, it is clear that Te Rauparaha understood very well that his fate lay in the hands—or, perhaps more accurately, in the genitals—of the woman who sat above him. He was fearful lest the barrier between himself and his would-be captors be interfered with; he knew that if the karakia were able to upset the spiritual potency of the vulva, its power to protect him would be nullified. It would become a ‘tara wāhia’—it would break open, disclosing the contents of the dark pit beneath. Instead of the kūmara pit acting as a whare tangata, enabling him to be reborn into Te Ao Mārama (as eventually occurred, once the Waikato ope had moved on and he climbed triumphantly back to the light of day), it would become a pit of death, the place where his life would certainly be brought to a swift end.” (Dr Ani Mikaere, doc A17, pp 11-12)(external link)

- “We are the kaitiaki / guardians of the passage of life and death. ‘Te Wheiao ki te Aomarama’ expresses this perfectly! The birth canal of the whare tangata is one area and experience where we feel the potency and power of the force of the wahine as we push our peepi into the world of light.” (Aorangi Kawiti, doc A24(a), p 7)(external link)

- “The fact that I am a woman and that I have te whare tangata, means that I have a responsibility to care for my body because of the requirement and the expectation that I will bring new life into this world. There is a dependence on me to ensure that te whare tangata that is within me, creates and ensures ongoing human life in this world.” (Patricia Tauroa, doc A60, p 17)(external link)

- “Te whare tāne is as essential to the creation of life as te whare tangata is. And te tapu o te tāne is not different from te tapu o te wahine in that if tāne and wāhine wish to bring into this world a child, then each needs to be mindful of the care of their own bodies, minds, and their own capability and capacities for the creation of new life and its care as that life grows, develops and is born.” (Patricia Tauroa, doc A60, p 20)(external link)

- “Who is it who dared to defined waahine as ‘te whare tangata’? That viewpoint in my opinion defines us as housing mankind with no reference to the process, the relationship with the creative powers and the counterpart in the creation. I believe we go further than te whare tangata. Waahine are the successors of the creation as well as the process. It is time for us to clarify our definition of ourselves and claim it all back as mana wahine tuku iho.” (Ipu Tito-Absolum, doc A70, p 4)(external link)

- “Although te whare tangata – birthplace of mankind – is strictly the domain of women, she cannot conceive without the help of a male: ‘mana wāhine and mana tāne come together to create mana tangata’.” (Lee Harris, doc A23, p 4)(external link)

- “I te wā o ngā atua, ka haere katoa ratou ki Te Pukenui o Papa, koinei te wāhi e kīa nei ko Kurawaka. Ko te whakamaramatanga–kei roto I te ingoa, kura - he momo taonga. Waka- he mea kawe I te tangata. Ko te wahine he waka, ko tāna he kawe I te tangata mai te pō ki te ao mārama. Ko te hanga o te wharetangata pēra I te hanga o te waka. Rongonui ēnei korero e kī ana ko te wahine he whare, engari ki a mātou e pēnei ana; ‘Ko te tane te kaiwhakairo o te whare, ko te wahine te kaiwhakairo I te tangata’.” (Te Motoi Taputu, doc A50, pp 3-4)(external link)

“In creating our world, the atua went to Kurawaka to the mound of Papa(tuanuku). The explanation is in the name, kura, another word for something highly valued. Waka is a vessel that carries people (analogy of a woman). A woman is likened to a canoe who is to deliver people from the unknown into this world. The construct of the uterus resembles that of a canoe. A well-known saying is a woman is a house, but to others is this adage; ‘Men carve houses, woman carve people.’” (Te Motoi Taputu, doc A50(a), pp 3-4)(external link) - “One example of the sacredness of the whare tangata is the belief that all the eggs that will be implanted in the daughter and grand-daughter are with the grandmother at the time of birth. This is an aspect of te ao Māori that emphases the generational links we all have ... Birthing was a sacred ritual that involved both male and female assistants with skills of whakapapa, karakia, and whanaungatanga. Karakia in particular was an essential part of the birthing process, and the mother is of the utmost importance throughout. Among those in attendance at the birth were those gifted in childbirth, and with an understanding of the anatomy for both mother and unborn child.” (Raiha Ruwhiu, doc A93, p 10)(external link)

- “The whare tangata is the house of humanity. Metaphorically speaking, the whare tangata is likened to the creation of Māori, from the time the Atua Māori were held in a warm embrace, and darkness, of their parents, Ranginui and Papatuanuku. This continued until their parents were separated, bringing the world into lightness, Te Ao Marama. This creation story is symbolic of the dark, warm embrace of the whare tangata (womb), where the baby is nurtured, until the baby is born into Te Ao Marama.” (Paihere Clarke, doc A141, p 6)(external link)

- “You cannot have whānau without whare tangata. Not only that. It informs us about who is coming into the world. It is basically about the creation of a child, and when they are born, it is about the Tikanga practices that go with it.” (Paihere Clarke, doc A141, p 7)(external link)

- “The life-giving role of wāhine as carrying te whare tangata (the house of the people) reinforced the necessity for women to be protected as it was critical in the continuation of whakapapa.” (Barbara Ann Moke, doc A38, p 5)(external link)

- “The whare tangata encompasses the female sexual and reproductive functions as one of many sources of strength. The power of wāhine, the whare tangata, the house of humanity. Our wāhine knew this sacred place and their sacred role of bring forth a new life.” (Paula Ormsby, doc A55, p 12)(external link)

- “The three stages of creation – Te Kore, Te Pō and Te Ao Mārama – [represent] a significant developmental period [in] connection to whare tangata. … Te Whei-Ao is a turning point, the transitional time just as the unborn child turns and engages into the birthing canal. This is in a space between Te Po and Te Ao Mārama. It is here that she draws on the strength of the realms to birth this child. The sacred strength of Whare Tangata. As the mother wails in this space calling forth her child from its sacred home of her whare tangata the same space in which one day this child when grown will karanga to those waiting at the waharoa. This karanga will clear the pathway of tapu from the gateway to the whare tupuna, the same way her mother called her forth from her whare tangata into Te Ao. She is regarded highly Tapu in this time and will remain that way until the pito has dried and fallen away. This process is called maioha.” (Paula Ormsby, doc A55, pp 13-14)(external link)

- “The centrality of birthing to our theory of creation serves as a constant reminder of the spiritual potency of the whare tangata. The process that brings each of us into being brought the world into being. Our very existence is centred around the sexual energy of women.” (Dr Ani Mikaere, doc A17, p 3)(external link)

- “Understanding the whakapapa of te whare tangata reveals the inextricability of women’s maternal bodies from that of perhaps the ultimate maternal body, that of Papatūānuku (mother earth). Through whakapapa each of us is united in a shared experience of residing in the womb space of Te Pō, moving through the various stages of Te Pō and finally being born into the world of light.” (Naomi Simmonds, doc A134, p 130)(external link)

- “The life-giving role of wahine as carrying te whare tangata (the house of the people) reinforced the necessity for women to be protected as it was critical in the continuation of whakapapa, (tuakana teina, mataamua, potiki) and age (kaumatua, pakeke, rangatahi, tamaiti, pepe) more than by gender.” (Barbara Ann Moke, doc A38, p 50)(external link)

- “Our wāhine are central to ensuring the continuity of our hapu by carrying the whare tangata of all future generations. Our wāhine also carry the mana and tapu around protecting the whakapapa, history and stories of relationships and connections and birthing practices through karakia, waiata and rongoa. This is the realm that has been given wāhine by our Tipuna Atua and our Tipuna Wāhine.” (Tracy Hillier, doc A92, p 15)(external link)

- “The strength of wāhine Māori formed part of the core of Māori existence, and was sourced in the power of wāhine sexual and reproductive functions. Māori culture holds wāhine in high regard as we are the whare tangata. The wāhine reproductive organs and the birthing process are important as they create our whakapapa. This is sacred in Tikanga. This is reflected in the womb symbolism of Te Kore and Te Pō and in the birth of Papatūānuku and Ranginui’s children into the world of light, Te Ao Mārama.” (Jane Ruka and Te Miringa Huriwai (A53(a), p 2)(external link)

- “The significance of te whare tangata for the mana of wāhine is that men must acknowledge their dependence on women if they are to ensure that their whakapapa is to continue.” (Patricia Tauroa, doc A60, p 19)(external link)

- “The duality of a number of kupu Māori illustrates the reproductive importance of women within the wider whānau, hapū and iwi. For example, hapū can mean to be pregnant or sub-tribe. Whānau can mean to give birth or family. Whenua has a dual meaning of placenta and land. Perhaps the term that highlights this most clearly is te whare tangata, which can mean womb and house of humanity.” (Naomi Simmonds, doc A134, p 16)(external link)

- “Koia nei ka whakapakuhatia te wahine kua puta he uri e whai pa ana ki ngā whenua o tetahi kē. Ko ia a Papatuanuku!!” (Hera Black-Te Rangi and Mareta Taute, doc A116, p 16)(external link)

- “The pūrakau of Maui seeking immortality for humankind is one that speaks volumes to the strengths of Hine-nui-te-pō (the ancestress of death) and the power that is held within te whare tangata.” (Sandra Corbett, doc A45, p 3)(external link)

- “The whare tangata (womb) is seen as a sacred repository for Hine, in the form of Hineteiwaiwa, who oversees the female reproductive cycles. It is the space where the divine and human come together. It is a portal for souls to enter this world.” (Mereana Pitman, doc A18(a), p 9)(external link)

- “Māori refer to wāhine as te whare tangata (the house of humanity), recognising the vital roles wāhine play in providing life and nurturing future generations. Wāhine are respected for our ability to create life, so we are treated with the same consideration as Papatūānuku, the creator of all life. Terms associated with te whare tangata are synonymous with the land.” (Te Amohia McQueen, doc A52, p 4)(external link)